L’Atlas Farnese est une sculpture romaine du musée archéologique de Naples. Elle date du IIe siècle de l’ère chrétienne mais serait une copie d’une statue grecque beaucoup plus ancienne. La statue représente le Titan Atlas portant sur ses épaules non pas le globe terrestre mais la sphère céleste où s’inscrivent les figures du Zodiaque. Après sa victoire contre les Titans, Zeus a condamné Atlas à supporter pour l’éternité la voûte du ciel. Dans l’Antiquité, on pensait en effet que les étoiles étaient toutes situées à la même distance sur une sphère entourant la terre. Leur position servait aux voyageurs, en particulier les marins, pour se repérer pendant leurs déplacements.

Géographie et astronomie étaient alors indissociable. On regroupait sous le nom de Cosmographie l’étude des sphères terrestres et célestes (Cosgrove p. x).

Constellations

Sur cette photographie centrée sur la sphère que porte Atlas, on reconnaît en relief les symboles de 41 constellations, dont 38 ont pu être identifiées parmi les 48 que cite Ptolémée dans l’Almageste, son traité d’astronomie écrit à peu près à la même époque (on compte actuellement 88 constellations).

Des lignes imaginaires, mais rationnelles et à finalité pratique

On distingue aussi en relief sur la sphère plusieurs lignes : les cercles arctique et antarctique, l’équateur et les tropiques célestes, un des deux méridiens célestes et l’écliptique (le plan de l’orbite céleste autour du soleil). Toutes ces lignes géométriques sont bien évidemment théoriques, contrairement aux étoiles observables dans le ciel même si elles sont ici symbolisées par les signes du Zodiaque. Le globe que porte Atlas n’est donc pas une représentation du ciel étoilé tel qu’il apparaîtrait aux hommes. C’est une construction rationnelle et géométrique du monde dont le but majeur est de maîtriser le temps et l’espace terrestres et célestes.

Modèle géocentrique.

Ces lignes imaginaires correspondent aux anneaux des sphères armillaires, ces instruments fabriqués et utilisés dès l’Antiquité pour représenter et simuler le mouvement apparent du soleil et des planètes autour de la Terre, selon le modèle géocentrique établi par Ptolémée qui place la Terre au centre de l’univers avec les autres corps célestes tournant autour d’elle. Ce modèle sera dominant jusqu’à Copernic et son modèle héliocentrique.

La première représentation d’un globe ?

On parle souvent de l’Atlas Farnese comme de la plus ancienne représentation artistique en trois dimensions d’un globe qui nous soit parvenue. Pourtant, d’après l’exposition Le monde en sphères, en 2019 à la Bibliothèque Nationale de France, une petite sphère céleste en argent trouvée en Turquie serait plus ancienne de quatre siècles.

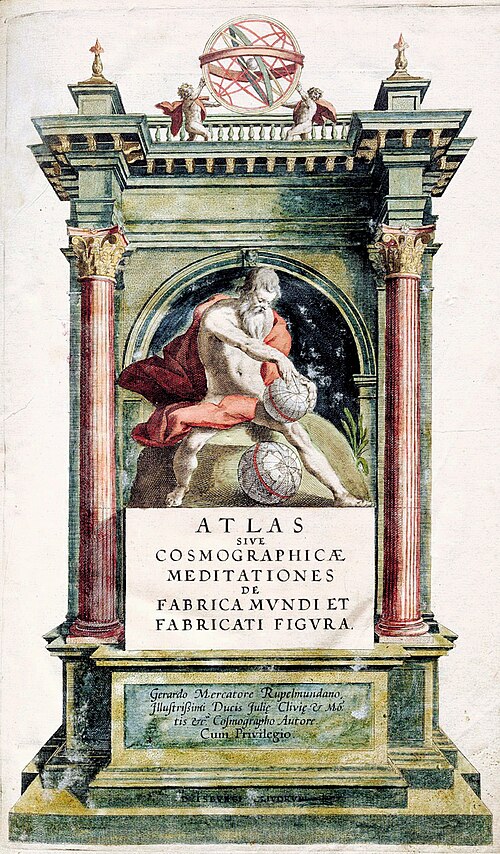

Atlas

Atlas est une figure complexe de la mythologie grecque. Pour faire (très) court, Zeus exile le Titan déchu aux confins du monde grec, et le transforme en montagne, l’actuel massif du même nom qui va de l’Algérie au Maroc et culmine à plus de 4000 mètres. Les « Colonnes d’Atlas » avec lesquelles le Titan vaincu supporte la voûte céleste se trouvent au niveau du détroit de Gibraltar entre la Méditerranée et l’Atlantique. Atlas a la réputation d’initier les hommes aux mystères de la terre (géographie) et du ciel (astronomie). En frontispice de la collection de cartes devenue célèbre après sa mort, le grand cartographe Gert Mercator a représenté Atlas consultant un globe et le nom du Titan est devenu le nom usuel de ce type d’ouvrage.

Atlas et Hercule …

Dans la mythologie grecque, les «Colonnes d’ Atlas» portent aussi le nom de «Colonnes d’Hercule ou d’Héraclès». En effet, un des travaux du demi-dieu, la recherche des pommes d’or dans le jardin des Hespérides, le conduit sur les pentes du Mont Atlas. Hercule propose de porter la voûte céleste à la place du Titan (aidé par Athéna) pendant que ce dernier ira cueillir les pommes. Mais à son retour, le Titan refuse de reprendre sa charge. Hercule doit alors utiliser la ruse pour lui rendre la voûte et récupérer les fruits précieux. Petites ou grande, c’est toujours une histoire de sphères … (BNF).

… et leur descendance

Dans son livre magistral sur l’imaginaire des globes dans l’histoire occidentale, Apollo’s Eye (L’œil d’Apollon), le géographe Denis Cosgrove évoque l’Atlas Farnese et cette «figure humaine soutenant le cosmos (…) qui se tient à la jonction du ciel et de la terre, à la fois divine et humaine». Pour lui cette figure peut être aussi bien Atlas, le gardien de la limite occidentale du monde antique, que Hercule, le héros armé d’une massue et couvert d’une peau de lion – dieu, homme et bête tout en un – allé à l’Ouest jusqu’au-delà du couchant, «aux limites extrêmes de l’espace et du temps (…) » (p.30).

Pour Cosgrove, cette collaboration mythique entre deux êtres légendaires donne naissance à une longue et constante affinité entre le globe et la pensée et l’imagination occidentales, qu’il nomme «l’œil apollinien» 1 :

De l’extension presque téméraire des frontières par Hercule et de sa prise en charge temporaire du fardeau cosmique d’Atlas découle une généalogie complexe qui s’étend d’Alexandre de Macédoine, qui revendiquait une descendance d’Hercule pour structurer son propre mythe d’empire mondial, à la Rome d’Auguste, au Portugal et à l’Espagne au XVIe siècle et au-delà» (p.30)

Titan et Hercule seraient les premières figures à incarner cet œil apollinien sur le monde «synoptique et omniscient, intellectuellement détaché», que de nombreuses autres adopteront au cours des siècles pour affirmer une autorité territoriale : églises, rois, empereurs, États et compagnies … (Cosgrove, p.5). On notera le paradoxe de la voûte céleste, représentée comme une sphère distincte du personnage qui la porte et qu’elle enveloppe pourtant. Bien sûr, ces êtres d’essence divine ne sont pas soumis aux lois physiques des simples mortels. On devine cependant que la vue du globe terrestre pose toujours cette question : où peut se trouver sur la Terre celui qui serait en capacité de la saisir dans sa totalité ?

Sources

- Documents

- L’Atlas Farnese sur Wikipedia

- Atlas (mythologie) sur Wikipedia

- The Farnese Atlas, Electrum Magazine 2016

- Livres

- Hofmann, C., Nawrocki, F., Engel, L. P., Bibliothèque nationale de France, et Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. (2019). Le monde en sphères : Bibliothèque nationale de France. https://expositions.bnf.fr/monde-en-spheres/

- Cosgrove, D. E. (2003). Apollo’s eye: a cartographic genealogy of the earth in the western imagination. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- «Dans la mythologie grecque et romaine, Phébus Apollon conduit le char doré du soleil au-dessus de la sphère terrestre, traçant l’arc diurne. Ses flèches, décochées sans passion depuis le firmament, apportent des calamités inattendues aux mortels.(…) Séparé mais non déconnecté de la terre, Apollon incarne un désir de totalité et une volonté de puissance, un rêve de transcendance et un appel à la lumière.» (Cosgrove p. 1) ↩︎

Ce billet vous a intéressé ?

- Consultez les billets SPHEROGRAPHIA d’espace&fiction

- Visitez le site du projet SPHEROGRAPHIA

- Et n’hésitez pas à partager et commenter !

The Farnese Atlas is a Roman sculpture at Naples Archaeological Museum. It dates from the 2nd century AD but is believed to be a copy of a much older Greek statue. The statue depicts the Titan Atlas carrying on his shoulders not the globe but the celestial sphere on which the figures of the Zodiac are inscribed. After his victory over the Titans, Zeus condemned Atlas to bear the vault of the skies for eternity. In ancient times, it was believed that the stars were all located at the same distance on a sphere surrounding the earth. Their position was used by travelers, especially sailors, to find their way during their journeys.

Geography and astronomy were inseparable at that time. The study of terrestrial and celestial spheres was grouped under the name of cosmography (Cosgrove p. x).

Constellations

In this photograph, which focuses on the sphere carried by Atlas, constellations can be seen in relief. There are 41 of them, 38 of which have been identified among the 48 listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest, the treatise on astronomy that he wrote around the same time (there are currently 88 constellations).

Imaginary lines, but rational and practical

Several lines can also be seen on the sphere: the Arctic and Antarctic circles, the equator and the celestial tropics, one of the two celestial meridians, and the ecliptic (the plane of the celestial orbit around the sun). All these geometric lines are obviously theoretical, unlike the stars, which can be observed in the sky, even though they are symbolized here by the signs of the zodiac. The globe carried by Atlas is therefore not a representation of the starry sky as it would appear to humans. It is a rational and geometric construction of the world, whose main purpose is to control terrestrial and celestial time and space.

Geocentric model

These imaginary lines evoke the rings of armillary spheres, instruments manufactured and used since ancient times to represent and simulate the apparent movement of the sun and planets around the Earth. They implemented the geocentric model established by Ptolemy, which placed the Earth at the center of the universe with other celestial bodies revolving around it. This model remained dominant until Copernicus and his heliocentric model.

The first representation of a globe?

The Farnese Atlas is often referred to as the oldest three-dimensional artistic representation of a globe that has survived to this day. However, according to the exhibition Le monde en sphères (The World in Spheres), held in 2019 at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, a small silver celestial sphere found in Turkey is believed to be four centuries older.

Atlas

Atlas is a complex figure in Greek mythology. To summarize, Zeus exiled the fallen Titan to the edge of the Greek world and transformed him into a mountain, the current mountain range of the same name that stretches from Algeria to Morocco and rises to over 4,000 meters. The “Pillars of Atlas,” with which the defeated Titan supports the celestial vault, are located at the Strait of Gibraltar between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Atlas is reputed to have initiated men into the mysteries of the earth (geography) and the sky (astronomy). On the frontispiece of the collection of maps that became famous after his death, the great cartographer Gert Mercator depicted Atlas consulting a globe, and the Titan’s name became the common name for this type of work.

Atlas and Hercules…

In Greek mythology, the “Pillars of Atlas” are also known as the “Pillars of Hercules or Heracles.” One of the demi-god’s labors, the search for the golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides, took him to the slopes of Mount Atlas. Hercules offered to hold up the sky for the Titan (with the help of Athena) while Atlas went to pick the apples. But when he returned, the Titan refused to take back his burden. Hercules then had to use trickery to return the sky to him and retrieve the precious fruit. Small or large, it’s always a story of spheres… (BNF).

… and their descendants

In his masterful book on the imagery of globes in Western history, Apollo’s Eye, geographer Denis Cosgrove refers to the Farnese Atlas and this “human figure supporting the cosmos (…) standing at the junction of heaven and earth, both divine and human.” . He cannot say whether this figure is Atlas, the guardian of the western edge of the ancient world, or Hercules, the hero armed with a club and covered with a lion’s skin—god, man, and beast all in one—who went west beyond the sunset, « to the extreme limits of space and time (…) “ (p.30). For Cosgrove, this mythical collaboration between two legendary beings gave rise to a long and constant affinity between Western thought and imagination and the globe, which he calls ”the Apollonian eye » 1:

From Hercules’ almost reckless extension of boundaries and his temporary assumption of Atlas’ cosmic burden derives a complex genealogy stretching from Alexander of Macedon, who claimed descent from Hercules to structure his own myth of world empire, to the Rome of Augustus, to Portugal and Spain in the sixteenth century and beyond » (p.30)

For Cosgrove, Titan and Hercules were the first figures to embody this Apollonian view of the world, “synoptic and omniscient, intellectually detached,” which many others would adopt over the centuries to assert territorial authority: churches, kings, emperors, states, and companies… (Cosgrove, p.5). Note the paradox of the celestial vault, depicted as a sphere distinct from the person carrying it, yet enveloping them. Of course, these divine beings are not subject to the physical laws of mere mortals. However, we can guess that the sight of the globe always raises the question: where on Earth could anyone be located who would be able to grasp it in its wholeness?

- Work Title/Titre de l’œuvre : Atlas Farnese

- Author/Auteur : Unknow

- Year/Année : 2ème siècle ap. JC

- Field/Domaine : Sculpture

- Type :

- Edition/Production :

- Language/Langue : langue

- Geographical location/localisation géographique : Rome

- Remarks/Notes:

- Machinery/Dispositif : Globe (sphère céleste)

- Location in work/localisation dans l’oeuvre :

- Geographical location/localisation géographique :

- Remarks/Notes :

Bonjour,

ci-dessous quelques éléments pour compléter les sections sur le terme Atlas.

D’après ce que j’en sais, c’est G. Mercator (ou plutôt son travail) qui transfère l’idée et le principe de la collection scientifique à la collection de cartes géographiques, en s’inspirant du Titan grec Atlas – ce que vous mentionnez. Ce nom fut attribué à l’atlas, livre-collection de cartes planes de géographie, probablement parce que le frontispice de l’ouvrage de Mercator était orné d’une gravure représentant Atlas, et qu’il recouvrait l’idée d’universalisme, de monde universel (représentée par « l’atlas » dans sa version sphérique, une idée que l’on retrouvera plus tard chez d’autres auteurs, tels Elisée Reclus par exemple). Je me demande d’ailleurs si on peut considérer, et dans quelles mesures, la sphère en tant qu’atlas au sens de collection de cartes ; il y aurait une discussion intéressante à mener. Finalement, qu’est-ce qu’un atlas ? Quoi qu’il en soit, le terme sera rendu populaire, grâce à sa reprise par d’autres grands cartographes du XVIes tels que Blaeu.

Autre élément concernant la mythologie grecque. Chez Homère, Atlas est bien un être d’origine marine, chargé de maintenir les piliers – qui relient les espaces terrestres et célestes au niveau de Gibraltar ; des piliers qui seraient profondément ancrés au fond de la mer, pour soutenir toute la cosmographie… et dont le nom aurait servit d’inspiration pour dénommer l’Atlas, la chaîne de montagnes située au nord-ouest de l’Afrique (au Maroc actuel). Source : Atlas dans l’Encyclopédie Universalis.

Enfin, cette idée de poids du globe m’évoque aussi le mythe de Sisyphe d’Albert Camus (1942).

J’aimeJ’aime

Merci de ta contribution Françoise. C’est un sujet complexe qu’Atlas, dans la mythologie comme dans symbolique de la géographie. Le billet visait à donner un aperçu du contexte de ce globe très ancien. Le fait qu’un atlas pourrait être pensé comme un assemblage continu de cartes est une idée intéressante, qui se heurte au fait que la carte est par définition plane, ce que produit la projection. Avec les systèmes de visualisation numérique, le passage du globe à la carte se fait automatiquement en la projetant, mais si l’on reste sur un écran d’ordinateur, on perd la sphéricité.

J’aimeJ’aime

Pingback: Quand Tex Avery joue avec le globe terrestre | (e)space & fiction